Presented at ALIA Online 2015, 3 February 2015 in Sydney. A longer version with bonus references will be made available on the ALIA Online site. Slides are on Slideshare.

In March 1930 the Sydney Electrical and Radio Exhibition opened in a blaze of excitement. Aboard his yacht in Genoa, inventor Guglielmo Marconi triggered a radio signal that reached across the world and switched on more than 2800 electric lights at the Sydney Town Hall. ‘All in less than a second!’, exclaimed the Sydney Mail, ‘Here was magic!’.

According to the Sydney Morning Herald, radio had ‘eliminated time and distance’.

About a month later the British and Australian Prime Ministers spoke for the first time via wireless telephone. ‘These were days for the annihilation of time and space’, the British PM proclaimed.

Sounds familiar?

From railways to the telegraph, radio, and the internet, the progress of technology has often been imagined as a battle against time and space. Progress has been measured in the seconds we save, in the distances we conquer, in the barriers of terrain and politics we bridge.

Remember when we used to talk about the ‘Information superhighway’?

In the realm of information this march of conquest is accompanied by discussions of speed and scale, by adjectives such as ‘instantaneous’ and ‘seamless’.

And you don’t have to look too hard to find software and service vendors touting the promise of ‘seamless discovery’. Indeed, it turns out that ‘Seamless Discovery’ itself is the registered trademark of a video discovery platform used by Foxtel and others.

Technology promises instant access to information — a future beyond silos.

In the library world, seamless discovery is commonly associated with what are variously called ‘next-generation catalogues’, ‘web-scale discovery services’ or ‘discovery layers’.1

The idea is familiar and seductive. Instead of forcing searchers to construct multiple queries across a variety of databases, systems and interfaces, these services aggregate metadata from different sources and offer access through a single search portal.

A seam-free service is one that maximises ease-of-use.

We all know what such services look like, even if we’ve never used one. Search is no longer just a task to be accomplished in pursuit of a particular goal — to find a desired resource or piece of information.

Google has played a central role in re-engineering our understanding and expectations of online experience. Ours is increasingly a ‘culture of search’ where the technologies of discovery have become part of everyday life.2

It’s natural then that users of other discovery services will approach them with a set of expectations shaped by the Googlisation of modern culture.

It’s not just the simplicity of that single search box, it’s our faith that search will just work.

Every time Google responds to our query about some obscure piece of television trivia with 152 million results, we cannot fail to be impressed by the power at our fingertips. Every time Google predicts our query or customises our results we are beset with awe.

Here is magic.

Google’s dominance gives it immense power in presenting to us an image of the world constructed to it’s own secret formula. This power bears ontological weight — if we can’t find something on Google does it exist?

Of course we all want to make life as easy as possible for the people who use our services. The question is how the pursuit of a Google-like experience constrains our options and assumptions.

Metaphors matter. Pursuing ‘seamless discovery’ in the wake of Google means engaging with questions of politics and power.

Seams are not simply obstacles to a smooth user experience, they’re reminders that our online services are themselves constructed. There’s nothing natural or inevitable about a list of search results.

Mark Weiser, one of the pioneers of ubiquitous computing, argued against seamlessness because it made everything seem the same. Instead he imagined systems with ‘beautiful seams’ — that empowered users to manipulate their contexts and connections.3

As Mitchell Whitelaw notes ‘seamfulness is also an ethical and political stance’ — it’s a commitment to exposing the interpretative distance between our collection data and its online representation.4 There are opportunities here not only for transparency, but to explore alternatives to Google’s template for discovery.

Research into the visualisation of large cultural heritage collections has emphasised that search is only one way of representing a collection.

By focusing on the stylish minimalism of the search box, we discard opportunities for traversing relationships, for fostering serendipity, for seeing the big picture.

By creating experimental interfaces, by playing around with our expectations, we can start to think differently — to develop new metaphors for our online experience that are not framed around technological conquest.

My own Eyes on the past, which allows you to find your way into Trove’s digitised newspapers through machine recognised faces and eyes, is far from a practical discovery tool. But building on my earlier work using facial detection technology as a means of archival intervention, it opens up questions about the lives embedded within our collections — we see them differently, we feel differently.

A Google-like search experience offers utility at the expense of critique. Its technologies are black boxed, its assumptions obscured.

How can those of us in the discovery business create a buffer for critical reflection while still meeting user expectations? What can we do in a service such as Trove that supports many thousands of enquiries a day?

I’d suggest we start with an acknowledgement of our limits, an attempt to trace the edges and the fractures that are too often glossed over in our pursuit of seamlessness. Let’s start by admitting what Trove is not:

- Trove is not perfect

- Trove is not everything

- Trove is not a machine

Trove is not perfect

Trove is an aggregator. It pulls together metadata from a variety of different sources, applies some normalisation across the required fields, and sends the results off to be indexed.

With close to 400 million resources harvested from hundreds of contributors through an assortment of different pipelines, it’s inevitable that there will be errors and oddities.

If you want to see errors, of course, you can head along to Trove newspapers zone where the limitations of Optical Character Recognition are on display for all to see. Unlike some full-text databases, Trove exposes the raw output of its OCR processing.

Trove’s transcriptions are improving all the time thanks to the efforts of thousands of online volunteers who correct the raw OCR output. Astonishingly, more than 130 million lines of text have been corrected by Trove users, in what is rightly touted as a highly successful crowdsourcing initiative.

But it’s also important to put this effort in perspective. Enter ‘has:corrections’ into the Trove search box to retrieve all the newspaper articles that have at least one crowdsourced correction. At the time I wrote this, the figure was 5,273,600 or just 3.6% of the total number of newspaper articles in Trove. Despite their important efforts, Trove’s volunteers will never be able to produce a perfect rendering of the newspaper content.

But what is ‘perfection’ anyway? OCR accuracy is important only in so far as it supports the interests and activities of users. For the purposes of discovery the accuracy of common search terms such as names, places or events are likely to be most important. But if you’re undertaking an analysis of changes in language across time, a much broader range of words would be significant.

Accuracy is something that need to be assessed and understood within the context of a specific activity.

Services like Trove have to be prepared to expose configurations, assumptions and limitations so that users can understand the impact of these of their own research.

If we are developing resources to support the creation of new knowledge we cannot simply black box our tech and trade on trust.

That’s Google’s game.

QueryPic is a simple tool that visualises search results in the Trove newspapers zone. QueryPic lets you see patterns and trends across the whole database.

When did the ‘Great War’ become the ‘First World War’? QueryPic can be used to explore this shift in terminology, but if you examine the results closely you’ll notice a small bump in the graph indicating that the term ‘World War I’ was being used during World War I. Huh?

If you drill down through the results you’ll find that this is because Trove users have been busily adding the tag ‘World War I’ to selected articles, and by default Trove searches user tags and comments as well as article text. The bump is an artefact of Trove’s search configuration.

Trove’s primary function is discovery — to make it as easy as possible for people to find things they’re interested in. But the sort of fuzziness that supports discovery works against other forms of analysis. We should make these sorts of assumptions more obvious.

By showing our seams, exposing our imperfections, we have the opportunity to educate. As well as helping people use Trove, we can open up bigger questions about the way search works on the web.

Trove is not everything

There’s nothing natural about our cultural collections or their digital representations — they have been created by many acts of selection, neglect, vision, accident and planning.

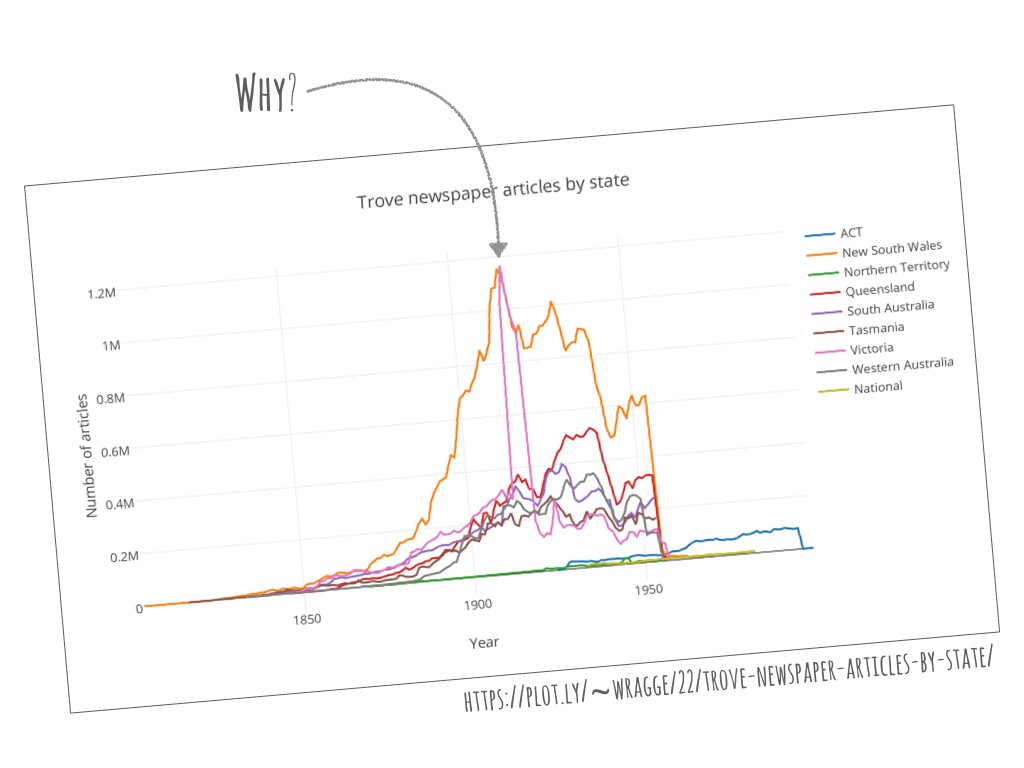

If you graph the number of newspaper articles in Trove by state and year you’ll notice a rather dramatic spike around 1914.

Why? Were more newspapers printed during the war era? The answer is simply funding. As part of the Australian Newspaper Digitisation Program, the NSW and Victorian State Libraries have chosen to invest in the digitisation of newspapers from the World War I period.

The contents of Trove’s newspaper zone, like any online collection, is constructed — shaped by many competing priorities. The consequences of this process are not always obvious.

In a competition for resources what gets digitised and why? There’s a danger that the sheer scale of aggregation services like Trove will reinforce existing prejudices. People already struggling for visibility and recognition within our cultural record might be lost amidst the overwhelming numbers of the safe and the sanctioned.

If we are concerned with absence as well as inclusion, with addressing the silences within our cultural record, we need to wary of sharing in Google’s aura of completeness. The ontological weight of search can too easily equate absence with non-existence.

But aggregation also offers new opportunities for analysis. Questions of representation and diversity can be explored through the metadata itself.

By way of a quick example, I used the Trove API to easily compare the languages spoken at home in Australia, according to the 2011 Census, with the languages of resources in Trove’s book zone.

It’s fascinating to consider how we might use socio-economic data to slice our cultural collections across the grain to reveal different patterns of access and exclusion.

By admitting the constructed nature of our collections, the gaps and the silences as well as their strengths, perhaps aggregations like Trove can become sites of both analysis and activism.

Trove is not a machine

Trove is not a single application, it’s a complex system with multiple components. This size and complexity focuses our attention on the technology — on the lines of code and racks of servers. But the system only exists to support human creativity and cooperation. Is it a machine, a community, or something else?

I often talk about Trove as a platform — it can be built upon in many ways, both through code and collaborations. In particular, by providing an open API, Trove invites the public to create new tools, analyses and interfaces.

But there are metaphorical dangers lurking here as well. Social media services such as Facebook and YouTube also describe themselves as platforms.5

If we are to embrace the ‘platform’ metaphor we must also be ready to unpack its implications. If we want progressive platforms we need to honestly address issues of openness, participation, and accessibility. Every API is an argument and no data is ever truly ‘open’.

For me the term ‘platform’ speaks of something unfinished — an invitation and an opportunity. Trove is permanently under construction, constantly improved through the labours of its developers and community.

This is most evident in the work of Trove’s text correctors, whose many small acts of repair help the technology to function more efficiently. But each tag or comment also changes Trove — aiding discovery, adding context, or creating new connections.

Other Trove-building activity is less visible, and the responsibilities more distributed. For example, Trove is currently working with Victorian Collections to bring many small, local collections from across Victoria into Trove.

But this collaboration is itself built on the labours of many people over many years — from the Museums Australia staff who train community groups, to the local volunteers who painstakingly digitise and describe their collections. Trove helps bring these efforts to the attention of the web, and is itself enriched.

For all the new terms we have for systems and devices we have thus far failed to find a language to describe online collaboration and social engagement. Instead we fall back on the awful term ’user’.6

By drawing attention away from ‘the machine’ to the many small acts that sustain and enlarge a service such as Trove, we create a space where language might evolve.

Broken worlds

Most technological futures are ultimately alienating and disempowering — people are cast as the passive consumers of the latest wonders and gadgets.

Instead of ‘progress’, Steven J. Jackson presents a vision of a fundamentally broken technosocial world, barely held together by numerous acts of concern, appropriation and repair.7 This focus on ‘repair’ helps us see the human agency at work, the possibilities for change.

What might happen if instead of seeing the seams and edges of our information landscape as speed bumps in the onward march of progress we recognised their fragility, and celebrated them as sites of collaboration, negotiation and repair?

What might we discover then?

- Joshua Barton and Lucas Mak, ‘Old Hopes, New Possibilities: Next-Generation Catalogues and the Centralization of Access’, Library Trends, vol. 61, no. 1, 2012, pp. 83–106. <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/library_trends/v061/61.1.barton.html> [↩]

- Ken Hillis, Michael Petit, and Kylie Jarrett, Google and the Culture of Search, Routledge, 2013. [↩]

- Quoted in Matthew Chalmers and Ian MacColl, ‘Seamful and seamless design in ubiquitous computing’, in Workshop At the Crossroads: The Interaction of HCI and Systems Issues in UbiComp, 2003. [↩]

- Mitchell Whitelaw, ‘Representing Digital Collections’, in Performing Digital: Multiple Perspectives on a Living Archive, ed. David Carlin and Laurene Vaughan, Ashgate Publishing, Farnham, UK, 2014. [↩]

- Tarleton L. Gillespie, ‘The Politics of “Platforms”’, New Media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, 1 May 2010. <http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1601487> [↩]

- Peter Lyman, ‘Information Superhighways, Virtual Communities and Digital Libraries: Information society metaphors as political rhetoric’, in Technological Visions: The Hopes and Fears that Shape New Technologies, ed. Marita Sturken, Douglas Thomas, and Sandra J Ball Rokeach, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2004, pp. 201–218. [↩]

- Steven J. Jackson, ‘Rethinking repair’, Media meets technology, MIT Press, 2013. [↩]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

“Seams and Edges”: @wragge on metaphors of search and politics of designing discovery interfaces http://t.co/BmoakI7szt… via @RoxanneShirazi

‘Seams and edges’ http://t.co/qAjvfz43B7 @wragge’s #online15 talk is worth a read. #musetech

What if we celebrated info landscape seams and edges as sites of collaboration, negotiation, and repair? By @wragge http://t.co/rstU88jGdM

Aggregation, acces & discovery in a broken world. Beautiful opening, important conclusions. By @wragge Worth the read http://t.co/30nyAPFTiu

“Seams aren’t simply obstacles to user experience, they’re reminders online services are themselves constructed.” http://t.co/B5oyFlV6df

.@wragge on systems with ‘beautiful seams’ – not blind search & retrieval – so we understand context and connections http://t.co/5vCzmJrlPy

a thoughtful and excellent piece on discovery: “Seams and Edges” from @wragge http://t.co/zVGdis7zUR

[…] concepts of repair, seams/seamlessness, and articulation in a very recent presentation called “Seams and edges: Dreams of aggregation, access & discovery in a broken world.” While a bit of a turn from what I’m thinking about here, it makes good reading and I’m grateful […]

From railways to the telegraph, radio, and the internet, the progress of technology has often been imagined as a… http://t.co/ClIfyepNCo

Seams and edges: Dreams of aggregation, access & discovery in a broken world http://t.co/pVG8BXTXtD ..ethics, faith & seamfulness..

Seams and Edges http://t.co/xiG2MEh29o by @wraggea a great read about visualisations, discovery and the limits and opportunties of it all

Challenging the supremacy of the search box: Seams & edges: Dreams of aggregation, access & discovery by @wragge http://t.co/4tfrd509to

@leilathebrave perhaps look at what @wragge says about experimental interfaces + serendipity in this http://t.co/O11vnVzEU9 @mollyhardy

[…] resources certainly speaks to each of these ideas. But, as Tim Sherratt pointed out recently, prioritizing seamlessness risks hiding underlying technology from users, possibly keeping them from developing a critical approach to ubiquitous technology, including in […]

This piece from @mchris4duke + @eosadler http://t.co/eyCWIJ787f goes quite well with @wragge’s http://t.co/O11vnVzEU9

“The ontological weight of search can too easily equate absence with non-existence.” @wragge’s “Seams and Edges” http://t.co/L9pRZyxcim

For those interested in the idea of the ‘seamless’ see @wragge on the subject here http://t.co/csMp992tjk #asaedge2015

More on beautiful seams. Read. http://t.co/iyPl8hkcJT

Seams and edges: Dreams of aggregation, access & discovery in a broken world https://t.co/duCkvJTTUJ via @instapaper